Initiating and Scaling-Up Community-Based TB care in Cambodia

Patients waiting for TB care at Kampong Ro Hospital, Svay Rieng when CHC began its work to treat TB in Cambodia in 1994

Step-by-step Cambodian Health Committee developed a community & patient-centered approach to cure TB across Cambodia and beyond

CHC’s Impact on TB 1994–2025:

From 1994 to 2024, Cambodian Health Committee (CHC) has provided community-based TB care to over 110,000 Cambodians in partnership with the Cambodian National TB Program (NTP)—with adherence and cure rates in approaching or surpassing 95%.

In 2024, CHC treated 11,361 people with TB across 13 provinces in Cambodia covering a catchment area of nearly 7 million people, achieving a 97% cure rate.

CHC initiated the countrywide program for drug resistant (DR)-TB in Cambodia in 2006 and scaled it up throughout Cambodia with the National TB program, transferring its management to the NTP in 2012. 2100 patients have been initiated on DR-TB treatment from 2006-2025. To learn more about CHC’s work in DR-RB, please click here.

CHC innovated provision of food with TB care in partnership with the World Food Program in Cambodia in 1994

CHC introduced innovative strategies into TB care—including the idea of patient supporters, treatment contracts, food supplementation, poverty mitigation, home visits, and patient travel support to pick up medicines—strategies which improved case detection, adherence, and cure rates, which have been widely emulated globally.

CHC pioneered linking microfinance strategies with TB care.

CHC scaled up Community TB Care (c-DOTS) in Cambodia with the National TB Program, which transformed Cambodia from one of the most TB-plagued countries in the world, to a global model TB treatment success. In Set 2025, CHC is delivering c-DOTS to catchment area covering 82% of Cambodia’s population.

Healing TB in Cambodia and the world

Tuberculosis is curable—whether in the world’s wealthiest countries or in its poorest. But in 1994 when Cambodian Health Committee was founded, the access to TB treatment and care in Cambodia was nearly nonexistent, a country, which had been ravaged by 2 decades of war, and where extreme poverty was widespread.

With a collapsed health system and poor access to care in a country of farmers at the time, Cambodia had become a global TB hotspot with one of the highest rates of TB in the world.

And at the time, it was widely believed by international agencies that poor, rural communities were incapable of completing the lengthy 6–8 month TB treatment that was necessary for cure.

Cambodian Health Committee (CHC) changed that. Starting from the ground up, CHC built a community-based TB program working in coordination with the National TB Program that overcame every barrier—delivering care through local health workers, bringing treatment to patients' homes, and proving that even the poorest could be cured with the right programatic support.

Our work is grounded in the belief that access to treatment for a curable disease like TB is a human right—and that with access to care and the right programatic support, anyone, anywhere, can complete the long and difficult treatment.

Our Origins: refugee camp to life-saving care in Cambodia

CHC’s roots trace back to the refugee camps on the Thai-Cambodian border, where survivors of the Khmer Rouge genocide fled in the 1980s. It was there in 1981 that Steve Miles and Bob Maat working with the American Refugee Committee (ARC) started a groundbreaking TB program -- whose radical approach introduced TB treatment contracts, TB education, food assistance, and patient supporters to TB care. And, they showed that refugees could be treated for this fatal yet, curable disease with stunning adherence to the treatment regimen and cure as they reported.

These data defied global expert opinions that argued that refugees with TB couldn’t be treated in a war zone—that they would not complete the 6 month treatment. As Steve Miles wrote at the time, and which is true today, “TB is…about a debilitating, lethal, contagious and curable illness”.

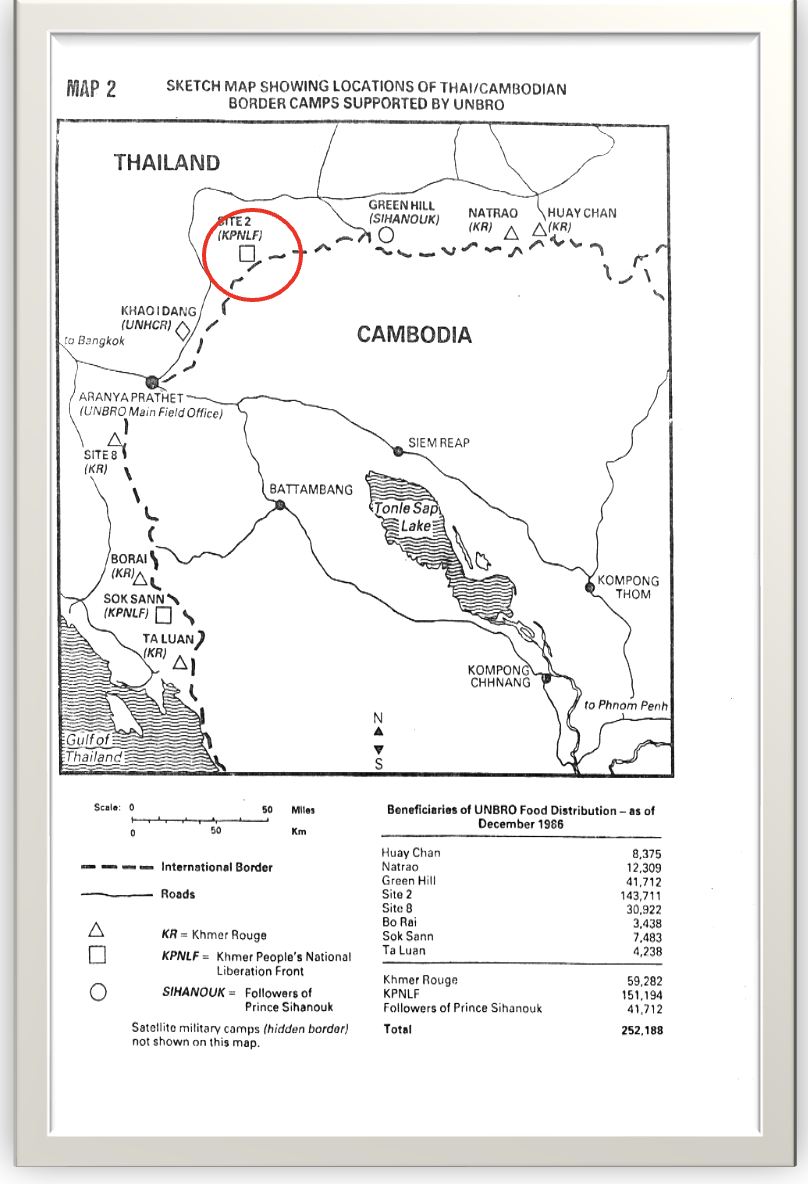

In 1989, co-founders of Cambodian Health Committee, Sok Thim, Anne Goldfeld, and Brian Heidel, met while working with the American Refugee Committee (ARC) at the Site II refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border (Site II is circled on the map below). Sok Thim, who graduated from ARC’s medic training program, was trained by Bob Maat and took over coordination of the TB Program at Site II. He was then secunded to the UN Border Relief Organization (UNBRO) where he supervised TB programs that had expanded to the refugee camps on the Thai-Cambodian border (graphic below). The ARC program would treat over 3000 patients in the border camps before the refugees returned to Cambodia.

The American Refugee Committee (ARC) TB program successfully treated thousands of refugee patients and pioneered daily observed therapy in refugee camps in an active war zone on the Thai-Cambodian border beginning in 1981.

Left: A map of the Thai-Cambodian Border in 1989-1990 showing the string of refugee camps straddling the border. Site II is circled in red. Top: An elderly woman under treatment for TB in the American Refugee Committee Bamboo Hospital in Site II in January 1990. Suffering from TB in her village of western Cambodia near Battambang (shown on the map), but unable to find treatment there, her two sons carried her to Site II for treatment to cure her TB.

In the early 1990s when the refugees returned to Cambodia, they found a country devastated by decades of war, which had no functioning health care system or effective TB treatment program. Even among those citizens who accessed TB treatment, only ~20% completed the required 6-month regimen for cure leaving them still sick, contagious, and susceptible to developing drug resistant TB.

In response, the WHO and French Red Cross advised Cambodia to require forced hospitalization for the first 2 months of TB treatment—a policy that was impossible for poor farming families, who couldn’t afford to leave their fields. Even after hospitalization, the long distances and cost of monthly medication pick-up meant patients often dropped out of treatment before completing the 6 month long treatment. Many never sought treatment until it was too late.

In 1994, with seed support from the Blue Oak and Christopher Reynolds Foundations, the Cambodian Health Committee (CHC) was launched and chose to work in Svay Rieng, one of Cambodia’s poorest provinces with the highest rate of TB infection in the country, to bring TB treatment to the people who needed it the most.

Building on the lessons learned in the life-saving refugee-camp program, CHC brought the transformative TB approaches of patient supporters, food supplementation, education about TB disease, treatment contracts, and observed consumption of TB medications to rural Cambodia in 1994, where at the time a family of 7 lived on less than $220/year and TB prevalence was among the highest in the world estimated to be ~900 individuals with TB/per 100,000 citizens.

CHC developed a new model in Cambodia working with the National TB Program: community-based TB care rooted in dignity, support, and science.

CHC’s work became a national health intervention — transforming TB care across Cambodia and influencing programs across the world.

A farmer with TB and fluid in his lungs in Svay Rieng Hospital, Cambodia. Photo by James Nachtwey

Bringing TB Care to post-conflict Cambodia

Meeting the situation in impoverished rural Cambodia, CHC developed and added new solutions to bring TB care to the community and to patient homes, including:

Food as Complementary Medicine: Pioneered with the World Food Program, CHC delivered monthly food packages with medicine pickups—now a global best practice.

Expanding the Role of Patient Supporters: Supporters, patients, and medical staff signed a treatment contract committing each partner to work together to achieve a cure. Patient supporters were trained to monitor daily therapy of TB medicine at home and accompany the patients through therapy.

Establishing Mobile TB Teams: CHC launched mobile health worker teams who visited patients at home, to check how the patients were managing to take their medications, while screening other family members for TB infection. If there was an interruption of therapy, the team strategizes with the patient and the supporter about any issues interfering with their TB treatment and how to overcome them.

Sun Sath, who was the head of the mobile TB team visiting a rice farmer at his home who had begun TB treatment in order to check on his progress on treatment. Svay Rieng 1997.

Active TB case finding in villages: Mobile CHC teams screened clusters of villages -- going house-to-house -- to find people who may be suffering from TB, rather than waiting for them to seek help at the health center. In this way, TB was be diagnosed and treated earlier, before the infection had caused irreversible impact on patients’ lungs and health.

TB HOME CARE by CHC mobile teams and patient supporters: This pilot approach involved mobile TB health teams visiting each patient in their home 5 days a week during the initial two-month intensive phase of TB therapy to observe the patient taking their TB medication with the patient supporter supervising the treatment on the weekends. Among 219 TB HOME CARE patients, 100% of patients took their mediation daily and their cure rate was 99%.

In rural areas patients often live far from the Health Center or Hospital. The CHC team on their way to visit a TB patient in Svay Rieng for a follow-up visit.

Linking Poverty Reduction with microfinance to TB treatment and case detection: Village banks focused on TB patients and families afflicted by TB, offered low interest loans based on the Grameen Bank model. And for example, among 590 TB patients who joined the village bank program between 1995 to 2000, TB treatment adherence and cure were each 100%, and loan payback was 100%. In the same period, a Village Health Fund was created from interest on loan payback that trained Village Health Agents in 96 villages, who performed TB case finding, spread TB health messages, and helped support patients through treatment.

The results of the CHC Program described above were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2004.

CHC’s community innovations led to the development with the Cambodian National TB Program of Community Daily Observed Therapy (or c-DOTS), which changed the trajectory of the TB disaster in Cambodia to one of great success in TB treatment and a global standout.

This young woman in far eastern Svay Rieng near the border of Vietnam, was found to have TB while pregnant, diagnosed by the CHC team TB during house-to-house screening for TB. She participated in HOME DOTS with her husband serving as her ‘patient supporter’ making sure she took her medicines for 6 months. A year later, the team stopped in her home to say hello and found her and the family doing well with her new baby boy who joined her 4 year old daughter (upper photo, right). With her health restored, with some seed money from a CHC donor, she bought a female water buffalo, which she rented out for farming and also bred, resulting in a baby buffalo (lower photo) improving the family’s economy, assets, and future.

Bringing TB care to those who live far from health centers: CHC’s Community TB Care/Community DOTS

Community Treatment or Community DOTS, as it came to be known, was piloted by CHC in partnership with the National TB Program in Svay Rieng and Kompot Provinces with support from JICA (Japanese International Cooperation Agency). In 2006 it achieved a 95% TB cure rate—a game-changing success leading to its national scale-up.

The Community TB Treatment model trained local volunteers—including former TB patients—to serve as treatment supporters, who volunteer to help neighbors stick to their daily medications by Daily Observed Treatment (DOTS) of the patient taking their TB medication. Thus, they are called DOT Watchers. It is a variation of the ‘patient supporters’ that Steve Miles and Bob Maat first conceived of and actualized in the TB Program on the Thai-Cambodian Border refugee camps.

The DOTS Watcher — many are former TB patients themselves — help the patient to make sure to take their daily medicine.

CHC’s mobile teams guide both local government Health Center staff, patients, and patient supporters/DOT watchers, through each phase of treatment, and through community trainings resulting in enhanced detection, education, and cure.

The CHC mobile team health worker (standing behind the patient) reviews the patient’s medical TB chart and checks on the patient at routine intervals to make sure treatment is going as planned and to evaluate any medication side effects. The CHC health worker is the link between the DOT watcher, the patient and the health center, combining all these energies to achieve cure of TB. Gaining weight on TB treatment is a very positive sign of curing TB, and is checked at every visit, as it is here.

The CHC Community DOTS pilot worked so well, it was adopted for nationwide scale-up in Cambodia by the National TB Program with support from the Global Fund for TB, Malaria, and AIDS.

The World Health Organization (WHO) credited the Community ‘DOTS’ TB model—that was developed by CHC — originally in Svay Rieng, then piloted by CHC in Svay Rieng and Kompot provinces between 2003-2006, and with the National TB Program scaled up throughout the country —for the dramatic reduction in TB infections in the country.

The young man in the red shirt was diagnosed with TB by the CHC Community DOTS team. He lived with his parents, wife and toddler son. The CHC mobile team screened the whole family in the household for TB including his young son. Screening of people in close contact with the patient for TB is facilitated by CHC Community DOTS, which is another advantage of this program.

CHC helped to transform Cambodia from one of the most TB-plagued countries in the world, to a global model of success in TB reduction.

This young mother is one of the +110,000 people in Cambodia that Cambodian Health Committee has treated for TB achieving cure rates in the high ninety percentiles. She is cured now of TB (photo above) and is very happy that her daughter, husband, and mother with whom she lives, did not get TB from her. With her health restored, she is looking forward to building her family and her future.

Healing the world one life at a time

Rice growing in Svay Rieng Province during the rainy season.